An essay by David Noble (Revised version 2009)

All images and text © David Noble. No image or text can be used for any purpose without permission

Above - Rocky Creek Canyon

I adopt a definition that a sandstone canyon is a creek that has cut a narrow slot in the sandstone. For the creek to be a canyon it must be significantly narrower than it is wide. Canyons can be horizontal - and then either dry or wet (with long pools and no banks) or more typically a small stream with sand and boulders and some sections with pools. Many canyons have vertical sections that require ropework in order to negotiate the canyon.

I have very little knowledge of whether aboriginals visited the Blue Mountains sandstone canyons. There are however, quite a few examples of aboriginal sites close to canyons. These include the cave close to the Bell Road near Mt Bell, the aboriginal rock art on the Tessellate Pavements north of Mt Wilson, sharpening Grooves and stone formations between Wollangambe and Dumbano Creeks, artwork in a cave near a small creek that flows into Bungleboori Creek (South Branch) and the cave at Deep Pass Clearing.

Probably the first canyons visited by white man included The Grand Canyon at Blackheath and Empress Creek that runs into the Valley of the Waters at Wentworth Falls. The interesting story of the construction of a tourist track along a ledge poised high above the Grand Canyon is described by Macqueen.

In the 1930's members of the Sydney Bushwalkers (SBW) tried to penetrate Arethusa Canyon from below. By climbing up some tree roots (no longer in place), these walkers could climb up the last abseil in the canyon and enter the horizontal section. They were however stopped by the waterfall further upstream. In 1940 Ken Iredale, a bushwalker from Hobart, Tasmania, passing through Sydney and a then member of the SBW, led a small group down the creek from the top. This first descent of a canyon is described in an interesting article by Col Gibson on the history of Arethusa Canyon.

Repeat descents of Arethusa Canyon followed in 1945 by the YMCA Ramblers (R Shumack et al) and Sydney University Bushwalkers (SUBW, Quentin Burke et al, 1946).

I'm not sure when some of the other canyons on the south side of

the Grose were explored. Some were looked at by walkers such as Marie

Byles in the 30's. For example, Rocky Points Ravine that forms Mt Hay

Canyon she called "Many Caverns Creek". It is possible that other

canyons in the area were explored by bushwalkers about the same time

- including Crayfish Creek, Hat Hill Creek, Alphius Canyon, Cut

Throat Canyon and Fortress Creek. It is also probable that Blue

Mountains residents such as Eric Dark, the pioneer rockclimber, also

visited some of these creeks. Eric Dark and his family used a large

camp cave located in a small creek south of the Fortress.

One has to speculate whether the residents of Newnes explored any of

the canyons in their valley. Certainly some such as Bells Grotto would

have been explored by surveyors working on the Newnes Railway.

In the early 50's, members of the Catholic Bushwalking Club (CBC) explored the bottom of Mt Hay Canyon and on one trip completed a rock climb up the cliffs near Butterbox Point. However it was a party from the Sydney Technical College Bushwalking Club (STCBWC - now known as University of NSW Bushwalkers (UNSWBW)) that first descended the canyon in about 1955. A few years later the CBC did go down the canyon and must have been unaware of the earlier descent. The canyon seems to have received the name "Butterbox Canyon" by the CBC. Other groups, such as SUBW, visiting this canyon in the early 60's all seem to use the name "Mt Hay Canyon" - the name used by the STC party. The interesting story of Mt Hay canyon will be told in the future by Col Gibson.

This group from STCBWC also pioneered some of the major canyons at Kanangra Walls at about the same time. According to Col Gibson, members of the group were looking for places to try out their newly acquired rope skills such as abseiling rather than going out to specifically do a canyon.

According to Geoff Ford who was active in SUBW in the late 50's and early 60's the club used to regularly go to Blue Gum Forest for a camp after exam periods and some of the members used to go via Arethusa Canyon. They were also familiar with Mt Hay Canyon. Col Oloman, who came as a migrant from England with his family to live in Lithgow was familiar with the western side of the Blue Mountains. Col was keen on visiting canyons and was perhaps the first to systematically look for canyons. One of the techniques Col used, and which has been used by subsequent canyon explorers was the use of stereo pairs of aerial photos. It was in this way that Col and two others, Gerry O'Byrne and Dick Donaghey found their way into Thunder Canyon in 1960. The discovery of the Carmarthen Canyons was responsible for a big impetus being given to canyoning. Col Oloman and others from SUBW also explored canyons in the Wollangambe Wilderness including Wollangambe Canyon and canyons in Dumbano and Bungleboori Creeks.

Above - Claustral Canyon

Also active in canyoning in the 60's was UNSWBW. One of its members, Rick Higgins, who had also been a member of SUBW, had been on early trips down many of the Carmarthen Canyons. Rick, through the Federation of Bushwalking Clubs, formed a "Canyons Committee" in 1963 to enlist the combined strength of many bushwalking clubs to systematically explore a large part of the Northern Blue Mts for canyons. During a meeting at Rick's house areas were assigned to clubs for exploration. These areas were all in the Wollangambe Wilderness. It seems that a few trips did indeed take place - but that the efforts fizzled out after a while. Perhaps due to the departure of Rick Higgins to live in Canada in 1965. Other clubs that took part in this exploration, included the Kameruka Bushwalking Club, The Coast and Mountain Walkers and the Sydney Bushwalkers. Many of these trips went unrecorded and it is likely that quite a few of the canyons in the Bungleboori Creek part of the Wollangambe Wilderness were found.

Chris Cosgrove of SUBW was active in the early 70's with exploring parts of the Wollangambe Wilderness. One canyon Chris found on a solo trip was in the remote Short Creek. Canyon exploration however received a boost when canyoners such as Tom Williams (Springwood Bushwalking Club (SBC)) and the author (SUBW and SBC) who were on a National Parks Association trip led by Ted Daniels in the Wolgan area. On that trip - Ted pointed out to the party the slot of a canyon (Heart Attack Canyon) and they later climbed up a new, unexpected canyon (Inverse Canyon). Ted, at that time, hadn't done any canyoning but both myself and Tom realised the potential of the area, which looked so similar to the Grose, for new canyons. Trips followed in the years 1976 to 79 and most of the major canyons in that area were explored. Personnel on the trips included bushwalkers from SUBW, SBC, UNSWBW, the YMCA Ramblers, The NPA and the CBC.

Chris Cosgrove, Tom Williams and the author were also on trips in the greater Coorongooba - Ovens Creek area during that time. These were normally extended walks visiting the major gorges during summer. On some of these trips, some interesting canyons were found. The remoteness and difficulty of access to that area meant that exploration for canyons was not very systematic. Some more canyons were found in the Wollangambe Wilderness as well.

In SUBW, the focus shifted back to the Wollangambe Wilderness. Bob Sault, Tony Norman, Doug Wheen, Ian Wilson and others started investigating more systematically the tributaries of Bungleboori Creek and the Wollangambe. Quite a few nice canyons were found. SPAN was another club that explored the area a bit later on. The CBC also explored some of the Wollangambe and Nayook Creek tributaries.

In the mid 80's, some of the SUBW walkers (Ian Wilson, Roger Lembit and Michael Donovan) came across Midwinter Canyon, a tributary of Numietta Creek, in the Northern Canyons area. Shortly later, Bruce Hamilton (SBC) and the author found some more canyons near Numietta Creek. On an Easter trip in 87, Tony Norman, Michael Glass (KBC) and myself found a major series of canyons flowing into Coorongooba Creek. Early trips into the area in the 70's and 80's had found canyons - some quite good, but they seemed quite sporadic. After this Easter trip - there followed more trips that located many more canyons, mainly on on the west side of Coorongooba Creek.

SUBW exploration continued in the Northern Canyons area. Another canyon exploration group also started exploring this area, and other areas. It included (another) Dave Noble (from Blackheath) and Glen Robinson - who both had caving backgrounds. They found a large number of splendid canyons - with little overlap with those found by the SUBW group.

Some of the canyon exploration led to a review of existing canyon

areas. New canyons were found in the Wollangambe, The Grose, The

South Wolgan and near Newnes.

In more recent years, with most of the major creeks well explored

- the focus has shifted to some of the very small creeks and the more

remote creeks in the Coorongooba and other areas. Canyon

explorers such as Andrew Valja have found some surprisingly

spectacular canyons in areas picked over by others earlier.

The earliest reference to the term "Canyoning" I can find is in the walks program of SUBW in 1963 prior to the departure of one of its members, Col Oloman for Canada. In a note, it describes Col as having been responsible for "starting our current canyoning craze". This suggests the term canyoning was in common use by bushwalkers around then. In quite a few references from the 60's and early 70's - the two terms "canyoning" and "canyoneering" seem to have been used interchangeably. Since the early 70's the term "canyoning" seems to have become the standard. This is similar to how "caving" has become favored rather than "caverneering".

The large cliffs of the Blue Mts are formed from Narrabeen Group sandstone. Only small amounts of Hawkesbury sandstone exist on top of the Narrabeen rock in a few places such as Mt Banks. The Narrabeen Group consists of two massive layers of sandstone separated by a narrow band of shale and claystones.

At the top of the Narrabeen Group is the Banks Wall sandstone. This is the layer that forms rock pagodas and forms the upper sections of canyon in many of the creeks. Canyons in the Banks Wall are typically short and narrow and with walls of limited height. Sometimes they are referred to as "prelude canyons" or "canyonettes". Some of these sections of canyon are quite significant however. Banks Canyon (partly named after the layer) in the Wollangambe Wilderness is nearly all in this top strata of rock and the nearby Froth and Bubble Canyon is entirely in the Banks Wall as is Fortress Creek Canyon.

Between the sandstone layers is the Mt York Claystone. This is the layer that forms the narrow halfway ledge that is readily apparent in formations such as The Three Sisters and also stands out in all the Grose Walls, the Wolgan Cliffs and the cliffs of the Capertee Valley. The National Pass walk near Wentworth Falls goes along the halfway ledge.

However, if a creek forms a canyon section in the Banks Wall, then there is often a non-canyon section of the creek stretching several kilometres before the creek starts cutting through the lower sandstone layer.

The lower layer of sandstone, the main canyon forming strata is known as the Burramoko Wall sandstone. A typical canyon often cuts into this layer with a waterfall going into a plunge pool. It is here that the canyon slot begins. For the canyoner - it is often necessary to abseil to descend into the canyon. The number of abseils can vary depending on the thickness of the Burramoko layer at that point as well as other factors. A typical canyon may have 3 or 4 abseils of a total height of 60m in this layer. It is not that common in the Blue Mountains sandstone canyons for an abseil to require two ropes - so most abseils (and hence waterfalls) are less than 25m in height.

Further north - in the section of the Blue Mountains east of Glen Alice, the Narrabeen sandstone is much less differentiated - and it is difficult to see where the individual layers are. Some canyons in this area feature ten or more abseils.

The presence of softer shale layers below the Banks Wall and below

the Burramoko strata probably plays a role on the formation of the

slot canyons. Bill Holland, in a PhD thesis for the University of

Sydney, has looked into this. Another factor, is the presence of

joints. These "cracks" in the sandstone typically lie in two

directions - perpendicular to each other and are readily apparent in

many canyons. Good examples of the canyon formation being controlled

by joints can be found in Surefire Canyon - where there are several

right angle bends near the third abseil. Joints are very easy to see

in air photos of areas such as Newnes.

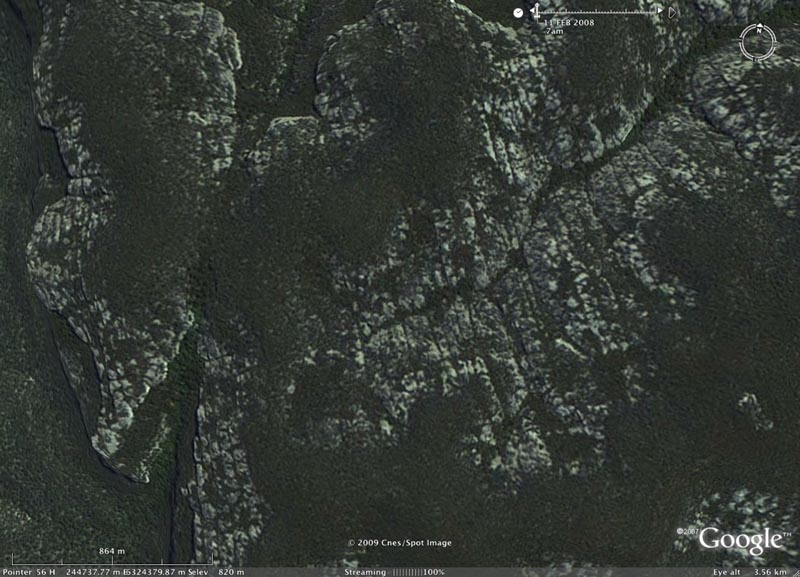

Above - Joint lines are very obvious in this Google Earth image of

creeks south of Newnes in the Wolgan Valley. Not that joint lines tend

to lie in one of two directions and that these two directions are

usually perpendicular.

The lower corridor of Whungee Wheengee Canyon clearly follows a

joint line. At the end of this straight section, the canyon carves a

right angle bend and joins Wollangambe Canyon.

Canyons seem to lie in a narrow band on the western side of the Blue Mountains Plateau. They start, in the south near Katoomba. All the Grose Valley west of Mt Hay lies in this band. I know of a few canyon tributaries on Wentworth Creek (and there may be more worth looking for there). Futher north, the band continues to the east of Tomah Creek and then through the Wollangambe Wilderness - generally west of Short Creek and Black Cliff Creek. Then Bull Ring Creek and Dingo Creek, and some eastern tributaries of Ovens Creek mark the boundary. Futher north, Blackwater Creek marks to boundary. On the west - the boundary is when the Blue Mountains sandstone thins out. There are many canyons in the Gardens of Stone National Park.

Southern GroseAll text and images by David Noble. © David Noble. Page

created 4 June 2000, modified 2009

No text or images can be used without permission from the author.